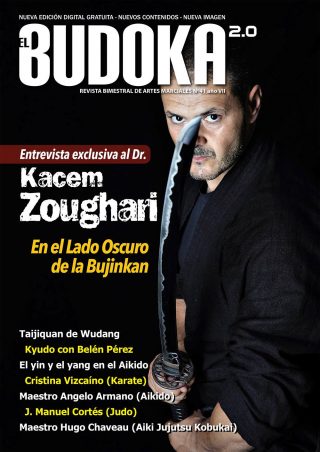

The dark side of Bujinkan- First part

Interview with Dr. Kacem Zoughari

(From spanish magazine “El Budoka 2.0” n°41 september/october)

Versione in italiano

To be able to count on the presence of the dr. Kacem Zoughari on the pages of “El Budoka 2.0” submits us to a challenge that we accept with humility and a certain pressure. His prestige, the vast knowledges, the virtuous reflexive ability, all of this lined up to a spectacular graphic material, needs an accurate, truthful and correct presentation.

Direct student of Tetsuji Ishizuka, studious of language, civilization and history of Japan of the national institute of language and civilization in Paris, the Dr. Zoughari is preceded by a well earned fame.

When he answers to any question, his answer doesn’t leave any place to doubts.

He knows what he has to answer and does it with no worries, without missing the truth.

Being a teacher of different universities, having a doctorate in philosophy and history of martial arts, being the winner of the scholarship Lavoiser of the ministry of foreign affairs, a military instructor for the special forces, expert in safety and techniques of self-defense…and also student, apprentice and instructor of classical martial arts and Ninjutsu, grant him a knowledge, a rigor and a tempering hardly achievable.

Our thanks to Dr. Kacem Zoughari for his time and to master Renan Perpinyà for his help and his collaboration.

Dr. Zoughari, would you sum us up your path in the study of martial arts?

Of course, it’s very simple. Nothing special, no important title or degree.

I began with the practice of Karate Shotokan when I was 10 years old, but I thought it was too limited. Later, when I was 13, I have practised Full Contact -I found it more amusing – but I had to quit. At age 14 I enrolled in a dojo in Paris. The person who managed the dojo said to teach the “ninjutsu” of the organization, known later, with the name of Bujinkan. Furthermore a big part of what I know comes from the observation of the different styles practised by some friends in the streets during my youth.

Which are the references of your professional path?

I have graduated in Japanese language and culture at the INALCO (National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilization), where I have realized all my university formation.

I have obtained different scholarships for research and analysis: Lavoisier, Japan Foundation, Toshiba, Etc.

I have progressively organized my activity I provided for different request: job of research in university ambit on the documents of transmission of the techniques of fight, strategies and military tactics, espionage, use of the body; but also jobs of translation, drafting of articles and books, as well as consultation.

I have realized conferences for different organisms and I have worked as a foreign associated researcher at the Nichibunken of Kyoto, in the Franco-Japanese section.

Now I’m dedicated to the writing of different works as researcher and independent adviser for different organizations.

You have known many masters and it still maintain solid relationships with some of them…

Yes, I’ve been to the meetings of a big number of masters.. Some of them have also introduced me to them to others and so it’s been for a while. It’s really difficult to maintain the contact with all of them but I do this for the important dates for them: New Year’s eve, change of season, birth, death, etc. I keep a cordial and respectful contact with some, with some less than the others. Or absolutely any contact. For what concerns different masters, it’s all about a report as a researcher, I’ve never considered myself as a student or disciple of none of them, neither I have ever assisted to their lessons as a student, but as historical researcher.

It’s important for me to make this point clear because a lot of people, inside and out of the Bujinkan, spreads incorrect information without not even knowing me or have asked to me or to the teacher that they believe I have frequented. In all thaose cases they cannot provide any clue.

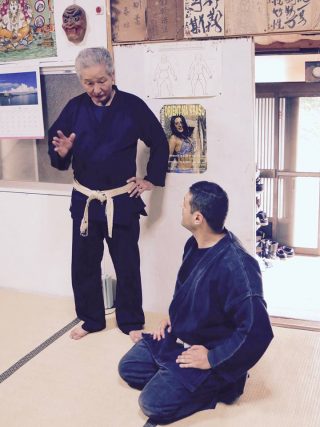

My student-teacher report is exclusively referred to Soke Masaaki Hatsumi and the Shihan Tetsuji Ishizuka.

As as a person who practices martial arts and as an historical researcher could you tell us the main differences between modern martial arts known as Gendai Budo and Kobujutsu schools?

This question by itself would be an excellent topic for doctorate (PhD) thesis. Anyway a serious and minute study would be needed. I’m my opinion it is difficult to answer in few lines since the different aspects are connected to the historical context, political, technical, to the transmission of the knowledge, to the relationship between teacher and disciple, etc… and they need a detailed explanation. In first place it would be necessary to define what we intend with Koryu (古流) it’s definition of according to the first historical mention of the term.

To all of this we would need to add an etymological and historical study based on more rigorous sources, on the terms Heiho or Hyoho (兵法), Bujutsu (武術), Bugei (武芸) Budo (武道).

Once we have understood the definition of term Koryu we would need to realize a study of all different Koryus of the historical periods of Japan, since the same term Koryu englobes three types of Koryu that spread and transmit a knowledge in according to a precise historical context, the vision of the fight and the strategies, military tactics, political and social changes and evolution that go with the economical development of the cities in times of peace or war…

As we can see, we can’t just answer such a complex question with a proper answer but empy in content.

What I do can sum up is that the main differences are the following ones:

- Differences in the functionality, in the use and in the role during the history of Bushis, or Warriors.

- Differences in the use of the body according to the weapons and if you had an armor, the culture of the regenerative movement, economy of the movement, the strengths’ management, use of the body without employment of brute force, biomechanics, ergonomics, etc.

- Differences in the methods of transmission of the knowledge, the relationship that ties the teacher to the disciple, the finalities and, obviously, the search of a sense in the practice itself.

So we can deduce that the fighting postures, as well as the movements, have experimented a process of adaptation during the Edo period (1603-1868), Meiji (1868-1912)…

Yes, the most ancient texts, the Emakis (絵巻), including sketches of attitudes of the body and, for extension, the use of the body and the weapons, show that these were completely different.

During the Sengoku period (Azuchi-Momoyama) and the Edo period (divided in 4 phases) the way to use the body as well as weapons, will experiment changes and they will evolve.

During the Sengoku period (Azuchi-Momoyama) and the Edo period (divided in 4 phases) the way to use the body as well as weapons, will experiment changes and they will evolve.

A ll these changes during a 300 year-old period will be propitious, during the Meiji period, for the birth of different disiplines of the Gendai Budo or sport of fight as Kendo, Judo, Aikido, Karate, Iaido, etc. that promote an use of the body that takes as a model a new vision of itself, deeply influenced by the western civilization.

Now in what kind of situation do you all find yourselves? Have the movements changed in the different schools out to the point of contradicting the directives of the founding masters?

There are various factors that bring to the change, to the modification -addition, omission, forgetfulness, loss, radical transformation, etc – of the knowledge of a teacher of a Koryu. As in the case of the question on the differences among Koryus and Gendai Budos, I believe that it would be wrong to answer in a superficial way if we consider for an instant the complexity of different factors whose nucleus resides in the human aspect, the relationship, the practice, the finalities, the research of sense, etc.

The change fundamentally engraves in the knowledge inherented in a Koryu. In fact it’s the mold, the heart itself of the knowledge included in the meaning of the kanji Ryu (流), whose meant it is “continuity.” Well. Therefore what continuous takes its own form from it’s historical period to fuse with it. In other words, adaptation always goes to hand in hand with continuity.

To answer the question it would be necessary to make an empirical and historical analysis of the documents of transmission and the use of the body in every Koryu, thing that, according to my humble opinion, would be impossible to be made circumscribing us to a simple question; and however contradicts this without studying the original documents in a sufficient way, would not be different than an impostor. On the other hand for the ones who respect numerous Koryu there is a radical change in the way to use the body and the weapons.

The reasons are mainly connected to the access to the knowledge itself, to the intention of the one who transmits, shows, teaches, explains, demonstrates… in some cases the use of the body, as well as the bodily attitudes, are so distant from what has been originally taught by the founding master that some of them focus entirely on the spiritual activities, practice dogma.

In other cases it’s the opposite.

There are even cases where the practice doesn’t preserve anymore the realism of the fight. Some others promote a moral education, transmission of values,etc.. So we can see the recurrent use of the term “traditional”, gave to the practice as a way to grant legitimacy, authenticity or truthfulness to the transmission of a practice. These tendences exist in all the styles, schools, organisations, etc…

By observing you as an practicioner we can say that your technique is absolutely unprovided of the typical protocols and rituals in the practice of the greatest part of those martial arts commonly called “traditionals” as in the case of Aikido, Katori Shinto, Muso Shinden Ryu, etc…

Be careful here…I’m not putting in the same plan tha practice of Aikido, with respect, witch the Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu and Muso Shinden Ryu.

If on the one hand there are some similarities in the Ceremony of these three disciplines, on the other hand there are also many differences and I believe that it’s important to respect the specificity of each of them. It’s important to know how to differenciate this according to an historical contexts and to the transmission between the different disciplines to find out more common points, in case they existed.

Before subsequently answering about the question I think it is important, even crucial, to know what we intend as “traditional”.

Because the problem resides in the etymological definition of term “traditional.”

This has turned into a sort of basket of decorations used for decorating the practice, to arrogate a certain legitimacy or authenticity to something that is nothing more than a mixture destined to deceive people motivated by a sincere wish to investigate and to practice, looking for a correct direction, a precise direction …. a search of sense.

In my opinion, if the protocol, the ritual or the label contradicts the essence of the practice itself; in other words if they estrange from the reality of the fight, from the precision and from the effectiveness, then they don’t deserve my attention.

I can understand and I accept the respect for the practice, for the place of the practice… the respect for the physical and mental integrity of the partner of training or the student. To know how to avoid to injure, entirely to show a superior ego or to make an exhibition of strength to impress or make sink the moral one of some student, etc.; I find this disrespectful and contrary to the essence of the practice.

Take refuge behind the label, the salute and whatever type of “ornament”, to establish useless hierarchies to avoid confrontation, to avoid answering, explaining or showing to someone – Being or not someone who practices – it is, according to my point of view, to the antipodes of the essence of the art of the fight. Both the science and practice of the Koryus have been originated from a deep experience lived during a fight and, therefore, it deals with having the abilities and the knowledge necessary to prove the value of what someone can show, promulgates or present in front of a professional fighter.

The historical reality of the first Koryus was so intense that there are many episodes, histories, chronicles and facts that represent them. Here’s the reason for studying history in depth and with precision. I have observed that the ceremony annihilates the effectiveness and therefore that same ceremony, label or protocol is used to limit the human relationships within the practice, atrophying the practice of Koryu, something deplorable.

I respect more the world of MMA, Boxe, Muay Thai, Competitive Judo and Karate that use at least a form of sparring or confrontation and therefore allows to get rid of the it ballast of label. To me, respect for the physical and emotional integrity of the student or the apprentice, respect for the order of transmission, for the technical application, the discussions and the critiques inside the rules of the art of the practice and of its different aspects are much more important than a bunch of protocols made without any sense, direction or orientation. We would simply imitate as monkeys a series of movements that doesn’t answer to the problems of our times.

I believe that the simplest label is also the most respectful; the one that allows to open the windows of our heart to the next one. It’s totally useless to overload ourselves in an excess of formality. Paraphrasing Ieyasu Tokugawa I would say: “life is as an excursion, you need to avoid the excess of equipment or you will end worn-out.” Therefore we can apply this protocol, ceremony, etc.

What does Budo Taijutsu consist in?

It is a generic word created by Soke Hatsumi. It’s important to understand the historical context of the use of this word…function of the use of the word, reasons and the finality that surround the choice of this.

The most amazing thing is that a big number of high grade people, Shihan and other instructors – even in Japan – don’t even know the history of the Bujinkan, of the word and the reason behind the choice of this; this allows to deduce that the way they study and practise the 9 techniques Ryu-has (classical Styles), as the respect towards the techniques, for the science of the fight, the form, etc. it’s questionable under many aspects. Additionally, in the ways of transmission of the science of the fight according to a Ryu-has, in any style, one of the fundamental aspects that unifies the master to the disciple manifests in the respect of the master’s knowledge. In other words, the practice under protection of a master consists of knowing the path, the steps of it, studying it and being deep into it.

It’s all about copying and exactly developing the techniques and the form as the master did, being inspired by him, etc. because to respect is to love and to love is to follow.

It doesn’t deal with imitating the master to strut in front of the students, to perform or to make a reputation. For example, buying a densho (伝書), documents of transmission of different Ryu-has, without being at least able to read them, to study them or even to explain them with only finality to have a collection and show off a knowledge, or to lie about the meaning and the history.

That is against the example that the master constitutes!

In my opinion, since I’ve seen Soke Hatsumi with his collection, I can say that he knows every and each densho that he possesses. Also he can propose you details about type of writing, style, grammar, kanjis, and even define the personality of the author.

To study is to re spect the knowledge; to practice means to give a deep importance to the respect of knowledge and also to the master.

spect the knowledge; to practice means to give a deep importance to the respect of knowledge and also to the master.

This allows to maintain a humble personality in front of the whole knowledge gathered by the master and to understand that the more we dedicate ourselves to knowledge, the more we practise, the more it’s necessary to dedicate to humility… an aspect that is practically absent inside of the Bujinkan and in many styles nowadays. This verification, this reminder, is fundamental to me because it allows us to understand why studying is important.

To get back to the question, the term Budo Taijutsu has been used for the first time in the book “Togakure Ryu Ninpo Taijutsu” where Soke Hatsumi explains that the essence of the 9 schools conforms a knowldge that he calls “Budo Taijutsu.” We can suppose that the choice of the term is at least prudent, avoiding to give explanations and technical specifications related to the Ryu-has to a public that could not understand them without the right transmission, or the precise practice besides the appropriate relationship with the master.

Obviously it’s very difficult to synthesize all the techniques, the thought and the history of the schools only in one work. That book as even been used for the editing of the famous “Tenchijin” that all the instructors have used as if it was a kind of “Bible” without even knowing the deep reasons for its editing, or the ones it has been written for.

The term Budo Taijutsu is composed by two words: “Budo” and “Taijutsu.” Both are generic terms that enunciate something with a very ample meaning by itself without really defining the depth or the specificity of a practice, discipline or Ryu-ha. “Taijutsu” means “technique of the body”, “techniques with the body” or “use of the body”, etc. as with Jujutsu, Kenjutsu, Ninjutsu, etc. we’re using a generic word. In fact we can say that Aikido, Karate, Judo, Boxe, etc. are taijutsu because in all these disciplines the body is used.

We’d need to add that there are different types of taijustsu: rigid, flexible, light, heavy, violent, forced, soft, void, ugly, beautiful, ballet dancer-like, etc. So we can understand and see what we want. There are Ryu-has like Takagi Yoshin Ryu that use the word “Jutaijutsu” to differentiate them from the other styles of harder Taijutsu…it also is the case of Asayama Ichiden Ryu Taijutsu.

The term “Budo” – as the terms “Bujutsu” and “Bugei” – it’s ancient, but it won’t appear until the beginnings of the Meiji period, when it will be used to legitimate or to grant a certain authenticity to the practice. According to the direction and the character of the master and the historical and political context will be used for privileging aspects as education, culture, a modernist view, a spiritual or even a nationalist aspect.

We should make an etymological study to show the evolution of the term, something that could not be done since we could fill 20 pages! Besides we need to clarify another point:

What is the meaning of the term “Budo” for Soke Hatsumi?

Because as well as the nature and the meaning of the word itself would be different according to the intensity of the practice and the study during a lifetime. He’s the only one who could answer this question.

His answer will change depending on the listener, on the context, on the topic, etc…

Under a linguistic profile “Budo Taijutsu” doesn’t have any meaning.

Under a linguistic profile “Budo Taijutsu” doesn’t have any meaning.

In Japanese, a teacher of Bujutsu, a soke Ryu-ha, none of them will understand it in a proper way since it deals with the vision and of the thought of Soke Hatsumi, that emanated the deep influence of Soke Takamatsu.

So translating the term “Budo Taijutsu” in an any language is a big mistake itself in my opinion.

In the Bujinkan the sense of this term varies, nowadays according to the apprentice.

If what he practices is shit, if what he does doesn’t have any practical utility, or fighting logic, any orientation or rational direction, if he practises something violent, hard, soft, void, “magic” or “mystical”, sporting, etc. or an unwatchable mixture of various styles, then that’s “his budo taijutsu”, his “vision” of the Budo taijutsu, etc. Until his movement it will be similar or it will be in line with the parameters of the form that the master practices – in this case, the 9 it Ryu-has of Soke Hatsumi – it will be a personal interpretation either in a good or in a bad way.

We should notice, also, that Soke Hatsumi used that term in the years ’90 of last century, during the first ten years of the actual one he used it very little and nowadays doesn’t use it at all.

He used mainly everything realted to Muto Dori and the aspects of the self-control founded on a deep self-consciousness.

In the Bujinkan are used to say “everyone has its own form because we’re all different”, “each of us develops its taijutsu depending on the feelings.”

But when you receive one “correction” from another apprentice of martial arts, the “feeling”, the “difference” and the “personal development” they all vanish leaving the place to the raw reality: but what have we been practicing all these years then?

I could keep on discussing more about it, of course but I think it’s enough with this.

(End of the first part)

Interview By El Budoka 2.0, Renan Perpinyà

Translation: Mariano Rodriguez

Adjustment: Shidoshi “Louis” Rocco Ventrella

Edited by Ninjutsu Padova – Tsukiyo Dojo Group

Comments are closed